Blair Pritchard is a Partner at Virescent Ventures and has led Virescent’s Seed, Series A and Series B investments in Hysata, on behalf of the CEFC. He also sits on Hysata’s Board of Directors.

The views expressed in this post are Blair’s personal opinions.

Why is Hysata important?

Hysata’s $172m Series B fundraise is the biggest Series B completed by any Australian startup, ever. What is Hysata and why is it an important company?

Blair Pritchard: Hysata is a company that designs and makes electrolysers for the production of green hydrogen. Green hydrogen is an important input into many decarbonisation pathways, such as fertiliser and chemicals. However, electrolysers to date haven’t been very efficient. They waste a lot of electricity as heat, meaning the green hydrogen produced is very expensive. Hysata is one of the first companies to change that. Its electrolysers are 95% efficient.

How does that compare with today’s electrolysers?

It’s a big leap forward. Today’s electrolysers waste about 25% energy in green hydrogen production, compared with Hysata’s 5%. That’s the kind of improvement the International Energy Agency wasn’t expecting until 2050!

So Hysata is making the world’s most efficient electrolysers?

That’s right. There are some solid oxide cells that are in the ballpark, but they require an operating environment of around 900 degrees Celsius and will likely compete with other users of waste heat – so they don’t compete economically.

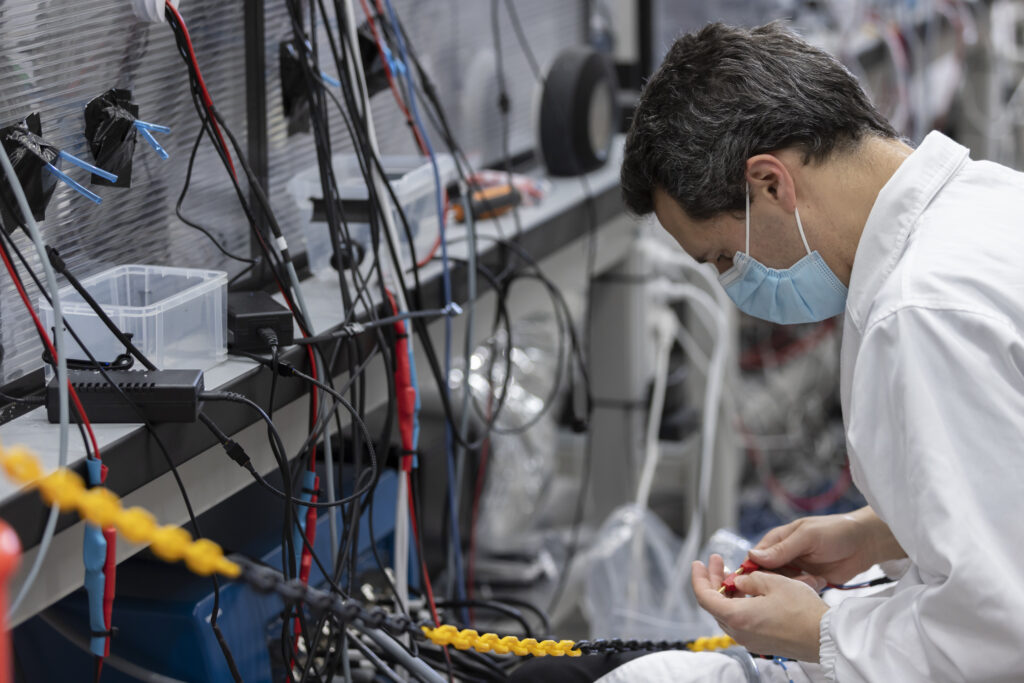

Behind the scenes at Hysata

What is the back-story to the Company and its technology?

It’s a spinout based on technology developed at the University of Wollongong. The CEO, Paul Barrett, and CTO Gerry Swiegers, worked together before. So, between them they have the academic publications and a lot of real world experience of hardtech commercialisation. They’d done it before and had some good experiences – and some that gave them thick skin (with someone else’s money, luckily).

This time around, they’ve done it their way. Even back before the company was set up, there was something very special, very grounded about their vision.

What are some examples of things Paul and Gerry have done differently this time round?

One example is they have learned that you can’t address the balance of system as an afterthought. The hydrogen passes through the balance of system to get to the customer, and that has a big impact on capex and unit economics among other things. So, they invested heavily in work relating to the balance of system around the time of the early cell designs, and that fed through to some big breakthroughs at the cell and stack level. Another example is they invested heavily in improving ease of manufacture, and that led to some big design changes early on. Another difference is they’ve really designed the technology to be hyper scalable, in terms of the choice of materials and manufacturing methods.

What is the culture they’ve built at Hysata?

Hysata has a very strong engineering culture. Although it’s still a young company, they’ve borrowed some DNA from Apple and they’re dead serious about shipping product that works first time out of the box. They’re also incredibly mission driven. Another aspect of the culture is the roots in the Illawarra region, where you have this amazing juxtaposition of heavy industry with stunning surf beaches and the escarpment. When you put all that together, it’s a great magnet for talent. They have a world class senior management team.

Defying hydrogen’s hype cycle

Hysata’s capital raise is particularly impressive given the heat (and hype) has come out of the hydrogen sector. What’s your take on the supply/demand outlook for electrolysers? How has Hysata managed to avoid the recent downturn?

If you look at the forward supply-demand balance for electrolysers, it looks like the market is oversupplied. So, on that logic, why would anyone want to own an electrolyser company? Conversely though, hydrogen is a US$100b+ per annum industrial commodity, and no-one is arguing we should keep making it out of coal (brown and black hydrogen) and methane (grey hydrogen).

So, someone is going to make a lot of money selling green hydrogen. As an aside, there are other low-carbon hydrogen models like pink and blue, none of which are so scalable that they fundamentally change the story.

Now, if you need to make green hydrogen, electricity is by far your biggest cost input, and if you can buy an electrolyser that uses 20% less electricity, you’re probably going to want to buy it. To link that back to your question about market dynamics, I can see demand for the most efficient electrolyser being very strong, even as a wave of consolidation goes through the producers of previous-gen technology.

The acid test is – what is the level of customer demand for a product? And if we look at Hysata’s customer pipeline, it really is extremely healthy. That’s what gives us comfort as investors, to be potentially number one in serving a large industrial market.

What will it take for green hydrogen to be competitive with hydrogen from fossil fuels?

Various studies have suggested the price of green hydrogen needs to get to about $2/kg to pave the way for widespread adoption. The Australian Hydrogen Market Study, developed by the CEFC with analysis from Advisian in 2021 suggested you could get there with about a halving of the then prevailing renewables costs, and a significant reduction in electrolyser capital costs. Since then, we’ve had all kinds of fluctuations in costs as well as huge subsidies to green hydrogen production in some countries.

My own personal view is that if a producer is using a Hysata electrolyser in conjunction with a gigawatt-scale combined wind and solar plant providing behind the meter power, $2/kg is achievable by 2030. In my personal view, if you’re looking, say, 3 years out at a 50 megawatt scale, an unsubsidised cost of $5/kg is more realistic, but you might be able to qualify for production subsidies that bring that down.

Could Australia use Hysata’s electrolyser technology to export its abundance of renewable resources?

Once you allow for domestic power demand growth driven by increasing consumption, population, and the need to “electrify everything” including transportation, my view is that quite a lot of renewable production capacity could be used up locally. That will tax our existing permitting regime quite a bit.

If we want to go a step further and start building lots of gigawatt-scale renewables in the desert, which not everyone currently supports, then my personal view is that the number one export product to make from green hydrogen would be fertilisers and fertiliser inputs such as urea. In my opinion, the number two option would be methanol, if you can find a CO2 point source, although green iron would be close. I think liquid hydrogen and ammonia are pretty hard to export. I see tech breakthroughs coming down the pipe but not enough to drastically change the economics for these.

Finding the next breakthrough climate technology

What other climate tech verticals do you think Australian startups can compete in strongly, and why?

One obvious example where we have invested heavily is in the next-stage processing of critical minerals, for sale as an input to overseas manufacturers.

But the biggest constraint on innovation is actually talent, and Australia has a competitive advantage there – we’re the only place the U.S. has a net migration outflow to, for example. So almost any business in an information economy vertical is one where Australia can compete. One example of that would be AI-enabled regtech which speeds up the permitting process for renewable energy deployment.

Energy is becoming another constraint – for example in powering new data centres to drive AI. The U.S. is looking to small nuclear reactors to power those, but I think we can get there for less than half the cost using firmed renewables, if we get the regulatory settings right. An example of tech that might work in that environment is data centres that are optimised to run on variable renewable energy, or perhaps partially powered by behind-the-meter generation.

What characteristics are you looking for in the next breakthrough climate technology?

Does the technology address a big, outstanding problem on the path to net zero? And do the founders have a ton of grit, resilience and entrepreneurial magic about them? On the flip side, the biggest areas where startups tend to fall down are not having big enough goals, or the founders not being cut out for it.

Got the next breakthrough climate technology that needs funding? Contact Blair Pritchard, Alex Oppes or any of the Virescent team members.